Emission caps and permit allocationintermediate

Two design features that vary across emissions trading schemes are how to set the cap on greenhouse-gas output, and how to allocate permits. These are important because they determine the overall ambition of the program, the obligation on participants and the scheme’s effectiveness at spurring decarbonization. A lower cap and more permits distributed for free mean less of an obligation, but the program is also less effective at driving decarbonization.

Key message

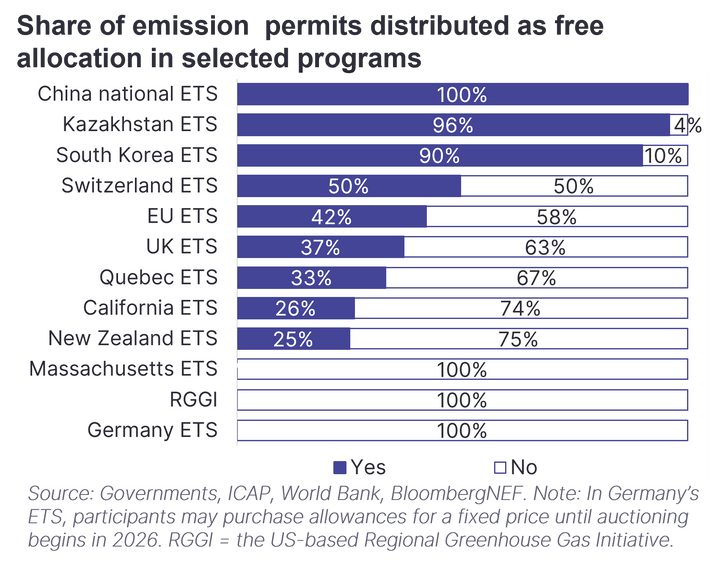

TThe type of cap and method for allocating permits help determine the overall ambition of a carbon market and its effectiveness at driving down emissions. A volume-based cap (like the EU Emissions Trading System) is meant to deliver a certain emissions reduction, while a cap based on intensity (emissions per unit of output) may allow more flexibility but could mean emissions rise. Governments often begin by offering a significant share of permits for free and later switch to auctions.

#Types of emission caps

The cap in a compliance emissions-trading scheme is the total number of allowances that a government supplies to the market, and defines the maximum emissions over a period of time for the covered sectors. The more common type of cap is an absolute cap (also known as a mass-based cap), which limits the overall volume of emissions permitted within each compliance period. Used by the emissions trading schemes in California, the EU and South Korea, this approach enables a government to align the ambitions of its carbon market with its broader decarbonization targets over time. It also guarantees a certain emissions-reduction trajectory, increasing certainty for investors and participants in the carbon market.

However, this approach also raises the risk of market shocks because it is challenging to forecast emission trends accurately and the fixed cap means it cannot respond to changes in the supply-demand balance. This was seen after the 2008-09 financial crisis significantly cut greenhouse-gas emissions and thus demand in the EU ETS. It was a major driver behind the 73% fall in the European carbon price to €7.6 per metric ton ($7.4/ton) between June 2008 and October 2009, and is one reason why most cap-and-trade programs now incorporate mechanisms to help control the market.

An alternative is an intensity-based cap, as been used by programs in China, for example. Here, there is no upper limit on emissions; rather, the government prescribes the number of allowances issued per unit of output – for example, ton of raw material, kilowatt-hour of electricity, or GDP. Participants can earn credits for emissions below their baseline and must buy credits if they exceed their target. One advantage of using intensity-based caps is that they allow more flexibility and accommodate for economic growth, and may therefore be favored by developing countries. However, they do not necessarily deliver a certain level of emission reductions, since absolute greenhouse-gas output can rise or fall according to economic activity.

Strictly speaking, the government does not need to set a cap – the approach initially taken by the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme. The program was not meant to limit domestic emissions and participants had no limits on the use of international carbon credits. The government also wanted to use the program to promote carbon sequestration from forestry projects. However, the absence of a cap made it hard to forecast emission reductions and weakened the policy’s effectiveness at promoting decarbonization. As a result, the government has now implemented an absolute cap.

#Permit-allocation mechanisms

Once a regulator has decided how many emissions permits to supply to a compliance carbon market, it can distribute these permits either by auction or free allocation – a concession that aims to make it easier for market participants to comply with the scheme.

Governments often offers participant in an emissions trading program at least some free allocation, which is calculated using two main methods: grandparenting or benchmarking. Grandparenting – when the volume of free permits is based on a participant’s historical emissions – is used in the Tokyo and Mexico schemes. While this approach is simpler, it weakens the incentive for companies to trade allowances and cut emissions early in the scheme. This is because lower greenhouse-gas output in a previous year reduces a participant’s free allocation in later years.

Benchmarking, however, should reward companies for early emission reductions, but is a more complicated method for participants and regulators, leading some programs to begin with grandparenting and then switch to benchmarking, as was the case in the EU ETS. With benchmarking, the volume of free allocation depends on performance standards, which may be set for a given product or sector, or at an average performance level or best practice. Benchmarking is also employed by the California, UK and Swiss cap-and-trade programs.

The aim of free allocation is to make it easier for participants, especially in the early years of a scheme, as seen in some Asian carbon markets. Free allocation may also be used to help avoid carbon leakage, by protecting participants from competition with firms in jurisdictions with less onerous environmental obligations. This is why free allocation continues even in established schemes like the EU ETS.

However, most governments seek to reduce free-allocation volumes as participants gain experience. For example, 2021 was the first year for 100% auctioning for the US-based Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, which only covers power companies. In the EU ETS, sectors less exposed to the risk of relocation will see free allocation phased out after 2026, from a maximum of 30% to zero by 2030. The EU is considering implementing a carbon border tax so it can still protect industrial sectors from international competition and also spur them to cut their emissions.

Instead of free allocation, governments may distribute permits via auctions, allowing the market to determine the price. This incentivizes cost-effective emission reductions, as firms with the cheapest abatement options will cut their greenhouse-gas output rather than pay for a permit. The highest bidders are likely to be companies with limited or expensive abatement options and they will theoretically be willing to pay anything up to their minimum cost of abatement per unit of emissions (normally measured in metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent).

Auction proceeds also raise revenue for governments, which can be spent on green infrastructure or vulnerable companies or consumers. The EU ETS, for example, auctioned over 57% of allowances in 2021, generating more than $34 billion of revenue – of which member states are legally obligated to spend at least 50% on climate action.

Stay up to date

Sign up to be alerted when the web platform goes live.