Offset quality and pricingintermediate

Compliance carbon markets like the EU Emissions Trading System are regulated by government bodies and permit prices are shaped by supply and demand. Offset prices, however, vary considerably due to the lack of an overarching regulatory body. Factors like the sector and location of the low-carbon project affect the price of offsets, but the biggest drivers are hard-to-quantify factors like additionality, permanence and measurability. These affect the quality of a carbon offset, with higher quality generally commanding a price premium.

Key message

Carbon offset prices vary widely based on the project sector and location, together with nebulous factors that are hard to define and measure. One such driver is project “additionality” – whether decarbonization would have happened without offset revenue.

The lack of regulatory oversight for voluntary carbon markets has created two main classes of companies purchasing offsets: those seeking the cheapest offsets possible, and those that will only purchase the highest-quality offsets and are willing to pay a price premium. The second type puts more emphasis on factors like co-benefits, additionality and permanence, and such players seek to purchase offsets locally in a sector that correlates with their business model (such as an oil company purchasing clean energy offsets). The distinction between these two types of buyers has meant that pricing in the offset market is more akin to a black box than a normal, functioning commodities market – an issue that will need to be resolved as demand begins ramping up significantly.

#Overarching trends

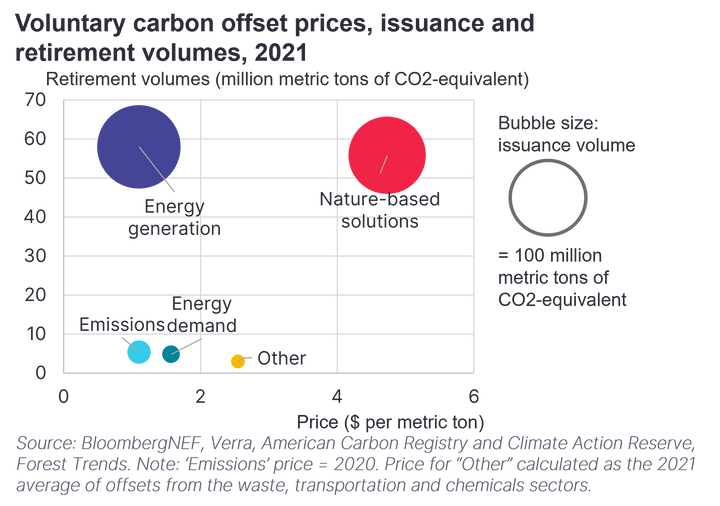

Unlike compliance offsets and permits, voluntary offsets are shaped by a range of factors. Emission projects, including carbon capture utilization and storage, as well as methane combustion, are often the highest priced today, due to higher technology costs. Nature-based solutions offsets are also among the most expensive, as they have higher additionality, remove emissions (in the case of reforestation) and could also have higher operational costs from monitoring forests, estimating emissions and physically planting trees. Energy generation offsets, on the other hand, have low additionality and, despite high demand, these offsets are among the cheapest.

The market a project is located in also has big implications for pricing, often due to the opportunity costs. For example, an avoided deforestation project in New Zealand or Australia is forfeiting revenue from the countries’ profitable agriculture sectors. This factors significantly into pricing. Operational factors can also have an impact – the cost of labor in markets like Canada and the US, for example, is often higher than in many developing countries.

However, there is no objective way to determine the quality of a voluntary carbon offset. This often means buyers have to work with a third party such as a broker, which can further complicate and lengthen the purchasing process. Many implemented projects might have other sources of revenue than offsets, making quality even less clear. For these reasons, voluntary carbon offsets are prohibited under some sustainability initiatives, although efforts to better differentiate quality in the offset market are well underway.

#Additionality

A low-carbon project is deemed to be ‘additional’ if it drives new, added decarbonization that would not have otherwise occurred had offsets not been monetized. Clean energy projects, for example, are already low-carbon energy generation sources with other vehicles for funding, like power purchase agreements and renewable energy certificates, meaning offsets do not always meet additionality criteria. To address additionality concerns, revenue from offsets is often used to fund expansion or improve efficiency of renewables projects. Revenue can also be used to switch from a dirtier source of power generation to a cleaner one. This is common in China, where revenue from offsets is used to fund coal-to-gas switching.

Conversely, revenue from offsets may lead to a direct reduction in emissions that wouldn’t have otherwise happened, such as the distribution of clean cookstoves in low-income communities or the planting of trees to store carbon. These nuances have a significant impact on a project’s ability to get carbon offsets verified, which in turn impacts prices. As a result, developers reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (known as REDD+), for example, have an easier time making this case, often claiming secondary and tertiary ‘co-benefits’, such as economic growth in local communities.

All projects need to undergo additionality testing in order to get their offsets listed on one of the four main registries – Verra, Gold Standard, American Carbon Registry and Climate Action Reserve. These tests can be project-specific and conducted by a third party, or standardized through a registry where a project is evaluated against a set of pre-determined metrics. Groups like the Integrity Council on Voluntary Carbon Markets are developing their own methodology, or ‘core carbon principles’ to measure and assess additionality.

#Measurability

The ability to measure emission reductions produced at a voluntary carbon offset project also impacts price. For emission-mitigation projects, companies can simply install sensors for greenhouse gases like methane to look at the data before and after implementation. On the other hand, measuring the decarbonization impact or number of offsets produced from a REDD+ project may involve satellite imagery or physical flyovers of a site to check on progress. These simple operational costs can drive up offset prices, though digital applications and technologies like drones can soften this impact. The emphasis on estimates in sectors like REDD+ also erodes the overall faith in such projects by market players.

#Permanence

Offsets are also priced based on how permanent they are, or how likely they are to be reversed. Certain projects are more at risk of having this permanence reversed than others. These risks can be as simple as a project developer going bankrupt, or more difficult-to-assess scenarios, like a forest’s exposure to wildfires, which can release any carbon stored from an offset project. Registries like the Verified Carbon Standard and Climate Action Reserve evaluate each project’s permanence, either on a project-specific basis or using a standardized approach.

Many projects have what is called a “buffer reserve” to address the issue of permanence, in which developers set aside a number of offsets to be retired if previous emissions were reversed. Projects with a higher permanence risk are often required to earmark more offsets for buffer reserves, driving up prices.

#Exclusivity

Though registries and exchanges have been established for the market, carbon offsets can still be difficult to track, and many buyers run the risk of purchasing credits that have been double-counted. This double issuance could be a result of a simple miscalculation by a developer or registry, or come as a result of accounting errors when two registries include the same offset or a buyer counts offsets toward an emissions-reduction target prior to retiring them.

Though these mistakes can be mitigated with more careful due diligence or the help of a broker, offsets may be more expensive if they come from a project with high exclusivity. Third-party verification companies have been established partly in an effort to address exclusivity, but it remains one of the major shortfalls of the voluntary carbon offset market.

Stay up to date

Sign up to be alerted when the web platform goes live.